Dotplot: a user-centric approach to early detection

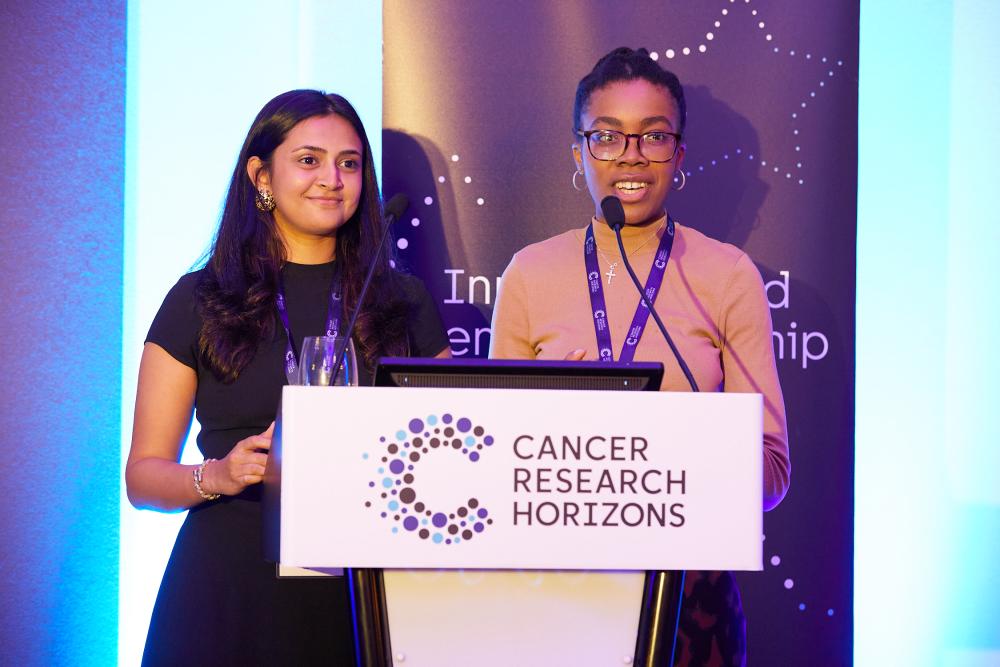

Dotplot, winner of the New Start-up of the Year at our 2024 Innovation and Entrepreneurship Awards, is developing a device to help detect signs of breast cancer from home. We spoke to co-founders Debra Babalola and Shefali Bohra about how they put their users at the centre of their creative process.

- 1 October 2024

- Tim Bodicoat, Science Writer

- 7 minute read

“If you’re trying to create something new, you probably don’t know how to do it yet,” says Shefali Bohra, getting to the heart of both the joy and terror of innovation. Probably more joy, in her case, because she and Debra Babalola managed to turn a master’s project into an award-winning start-up in a little over a year.

They are the co-founders of Dotplot, a tool to help people monitor their breast health from home. By combining a handheld ultrasound device with an app to guide you through a self-check, Dotplot aims to track changes in breast tissue and flag any abnormalities that require a visit to the GP.

With no comparable devices currently on the market, many women either rely on pamphlets and videos to show them how to do a self-check, or must wait until they’re over 50 when the NHS starts to offer routine mammograms. By making regular self-checks easier to do and track, Dotplot’s goal is to help detect breast cancer earlier.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK, with more than 150 new cases every day and over 11,000 deaths a year. If diagnosed at the earliest stage, almost all women with breast cancer survive their disease for five years or more. This falls to around 3 in 10 women when breast cancer is diagnosed at the most advanced stage. Any device that helps to catch breast cancer earlier has the potential to save many lives.

We’ve been engaging with women since the very beginning so we want to push it, we want to drive it.

Where it started

Shefali and Debra met while studying Innovation Design Engineering in a double master’s degree run by Imperial College London and the Royal College of Art. It was during a group project that the idea for Dotplot began.

Tasked with coming up with a product that could have a positive impact on society, the group were discussing ideas in healthcare monitoring when Shefali shared her experience of finding a knot in her breast. After her aunt, who is a doctor, advised her to do a self-check for the next 14 days and did a palpation exam, Shefali was reassured that it was nothing to worry about. But the uncertainty of self-checking left a lasting impression. “There’s so much subjectivity involved,” she says, “so much guesswork.”

They spoke to other women and found the problem resonated with them. What is normal or abnormal breast tissue meant to feel like? What did it feel like last month? Have I checked that area already? As many people will not have a healthcare professional in the family to turn to, the group focused on creating a product that would address this confusion.

Putting the users first

As product designers, Debra and Shefali put their users at the centre of the development process. “We were always taught to really understand your users,” says Debra, “the challenges that they’re facing, what they’re currently using to address their issues, and where the gaps are that you can fill.”

“Figure out five things that are troubling them,” adds Shefali. “If you tick all those boxes and take the product back to the user, they will give you another five points.”

This iterative, user-centric approach helped them find their concept from the vast pool of ideas they considered, ranging from a huggable pillow to a smart bra. “You can’t narrow down an idea too early,” says Debra. “You need to broaden out, think as crazy as possible and see what resonates with people.”

They also drew inspiration from unlikely sources. To see how people might track which areas of the chest they’ve checked, Shefali and Debra created a bra out of fidget poppers that users push in as they cover each section, and asked users to draw on themselves using a Pictionary Air pen to map out their chests. With more user feedback they found which elements they wanted to keep, taking the grid system of the fidget-popper bra and the interaction of the pen.

Once they had their first prototype, they entered Imperial’s flagship entrepreneurship competition, the Venture Catalyst Challenge. Although they were juggling their final thesis projects at the same time, they had the support of their tutors, verging on tough love in some cases.

“I remember one lecturer saying, if you’re going to be in the competition, that’s fine,” says Debra, “but don’t get into the programme and then not win something.”

Luckily for them, they did. They won the competition’s health and wellbeing track followed by the grand prize for a total of £30,000. With that injection, plus the skills and knowledge gained during the programme, they launched Dotplot as a business in March 2022. Less than six months later, with their graduation gowns barely back from the dry cleaners, they won the national round of the James Dyson Award.

I knew it would require a lot of perseverance, a lot of dedication and not looking back on what has gone wrong.

Overcoming challenges

On paper, Dotplot’s journey seems remarkably smooth, as they went from one accolade to another, picking up grants from Innovate UK and NIHR, and winning New Start-up of the Year at our 2024 Innovation and Entrepreneurship Awards, all within two years of launching. However, there are plenty of challenges hidden behind those trophies.

“Adapting it for home use is such a hurdle because it’s been reserved for clinical use for a reason,” says Debra. “It requires training to be able to check your breasts with this kind of tool so this is a key usability challenge for us to overcome.”

There are also business development challenges like protecting IP, navigating regulatory approval, and pricing, all made harder when creating a novel product. Shefali and Debra are applying the iterative principles of design to these business challenges as well: if something doesn’t work, try something else.

It might be daunting trying to commercialise a healthcare product without a medical or business background, but the Dotplot founders see this as a benefit, especially for something that will be used at home. They can’t guess anything about their users or the market they’re trying to break into. They have to be intentional about bringing users on board throughout their journey.

That’s not to say they’re ignoring external advice. Their next step after honing the user experience is to get clinicians on board. They’ve already hired a team of engineers and continue to build an advisory board of medical and business experts to help them do that. “We always surrounded ourselves with people who are key opinion leaders or have specific expertise,” says Shefali. If you’re a clinician, researcher or someone with a keen interest in healthtech who’d like to get involved, get in touch with Dotplot here.

They’re also testing the beta version of their app and are seeking participants to provide feedback and shape the future of Dotplot. Fill in this form if you would like to take part. The next step after that is to finalise the minimum viable product for their first clinical trial, expected in 2025. There are yet more challenges there, with the complexities of integrating all the hardware components into a device that matches their vision.

Despite these hurdles, Shefali and Debra remain committed to their users. “Because we’ve been engaging with women since the very beginning,” says Debra, “there's this expectation that this thing is going to be ready soon, and so we want to push it, we want to drive it.”

The entrepreneurial bug

Shefali comes from a long line of entrepreneurs and always wanted to start her own business. But how has it compared to her expectations? “I knew it would require a lot of perseverance,” she says, “a lot of dedication and not looking back on what has gone wrong, but always looking forward,” she says.

Debra was the opposite. She expected to be designing on client projects and didn’t consider launching a start-up as a career path. “I had lots of ideas about what entrepreneurship looked like in my head, which weren't very accurate,” she says. It wasn’t until she started her master’s that she thought it could be a viable option. “I saw there’s actually so much scope within it, and so much fulfilment that comes from building something from the ground.”

Whatever their preconceptions, they both appear to have caught the entrepreneurial bug, and that can only be a good thing for cancer care. Cancer is relentless, and finding new ways to detect and treat it requires as many different perspectives as possible – not just from researchers and clinicians, but also from product designers.

The Dotplot founders are taking all this in their stride. “Every day is basically a new day,” says Shefali. “Every day is basically a new set of challenges. And you just have to walk your way through it.”